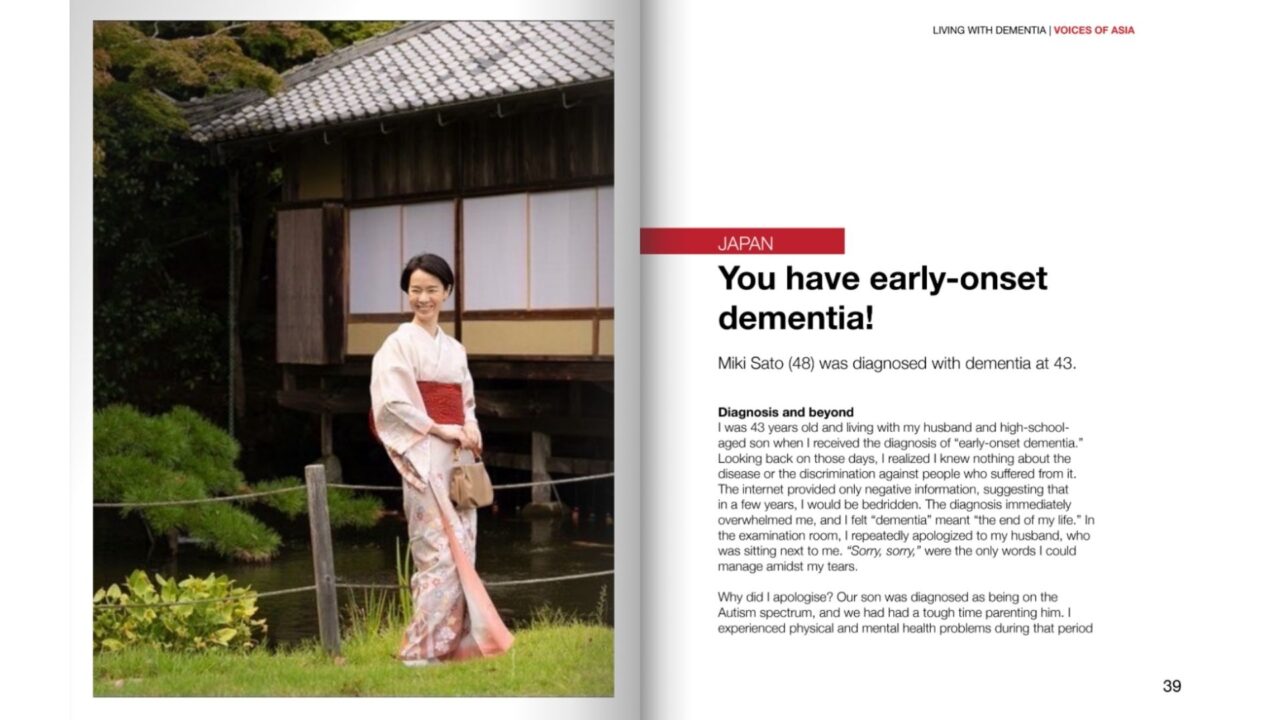

JAPAN | You have early-onset dementia! | Miki Sato | Living with Dementia – VOICES OF ASIA

Miki Sato (48) was diagnosed with dementia at 43.

Diagnosis and beyond

I was 43 years old and living with my husband and high-schoolaged son when I received the diagnosis of “early-onset dementia.” Looking back on those days, I realized I knew nothing about the disease or the discrimination against people who suffered from it. The internet provided only negative information, suggesting that in a few years, I would be bedridden. The diagnosis immediately overwhelmed me, and I felt “dementia” meant “the end of my life.” In the examination room, I repeatedly apologized to my husband, who was sitting next to me. “Sorry, sorry,” were the only words I could manage amidst my tears.

Why did I apologise? Our son was diagnosed as being on the Autism spectrum, and we had had a tough time parenting him. I experienced physical and mental health problems during that period and was repeatedly hospitalised. As my son became a high school student and grew up, my health gradually improved. This was supposed to be a time when we could look forward to our son’s future with hope, but now, because of my dementia, I would be a burden to my husband in his prime and my adolescent son.

My husband silently caressed my knees. I understood his message of love, “Don’t worry, I’m here.” I spent more than six months of my life shut up at home in deep sadness and despair. I was unable to care for my son, who was maturing so well, and I did not want to expose my family to my rapidly declining condition. I wanted to disappear before I became a burden to them. That was all I could think about.

A turning point

“I can’t keep doing this.” There were so many days when I was simply overwhelmed by this thought, but eventually I felt that I would like to meet people diagnosed with dementia and see how they were living their lives. One day, I encountered Mr Tomofumi Tanno, an active dementia advocate. I tagged his name on my Facebook page, added a self-introduction, and posted my comments. Through this, I met Mr Takua Morioya, manager of the daycare centre where I now work. Mr Morioya was concerned about me being confined to my home. Although he invited me to his daycare centre for rehabilitation, I could not bring myself to visit the facility. Nevertheless, he continued to send me thoughtful messages, and enquire about me. Finally, I was able to get myself motivated and I visited the daycare centre.

Mr Moriya’s daycare centre

Unlike the day-service facility I had imagined, this was a house in an established residential area, where clients enter with a smile and a cheerful “I’m home”, just as if they were home. Later, this daycare centre became a special place: one that inspired me to become more active. After I became accustomed to the centre and could enjoy myself there, Mr Moriya suggested I become a staff member. I could not believe this, and I asked him if it was really possible for a person living with dementia to work. Mr Moriya replied, “Regardless of whether you have dementia or a disability, here both staff and users are members, and we have an equal relationship.” This was a big turning point in my life.

The second chapter of my life

I am not who I used to be. I was diagnosed with dementia, but since then I have been given a number of new opportunities. I now work as a staff member at a daycare service, where I myself provide peer support for others. I lecture and write, and I engage in numerous other activities, including as an airport universaldesign team member. Furthermore, I re-started my spokesperson work for a company where the manager understands and accepts my condition (namely, that I live with dementia.) Through my many activities, I want society to understand the diversity of, and possibilities for, people living with dementia.

I feel that now is a most fulfilling and enjoyable time in my life. Of course, sometimes I experience much inner turmoil and hardship, and the anxiety brings me to tears. However, the following precious expressions give me courage: “Live in the present,” “Be myself,” and “Respect myself.”

Those living with dementia just got it a bit sooner than others. A diagnosis of dementia does not change us in any way. What changes, as a result of prejudice and discrimination, is the way people look at us. When a person with dementia can no longer speak properly, many people automatically think they don’t understand, or they can’t do anything. However, I have learned through my own symptoms and through my experiences at the daycare centre that people living with dementia still have words they want to say in their heads. When I have been unable to express my feelings or thoughts to my family, I have been frustrated and tearfully shout, “I have no idea. Yes, I am stupid.” Likewise, others may not always be able to speak as they want to or be able to express themselves appropriately. When I spend time with friends who have dementia, I can help those having difficulty with speech. Being close to them enables me to support them by looking for “hints” of their words, and little by little they can sometimes find and piece those words together, their faces beaming with smiles when they do so.

Those of us living with dementia are aware that our sense of time is different from others. This makes us feel uneasy, but even so, we desperately try to do our best. We have a lot of things we want to do for ourselves, and even if it takes longer, we are still happy with our sense of accomplishment when we manage it. If people understand our condition, when they support us with empathy and without rushing us, we can try to accomplish more, no matter if it is a little “dream” or just a small wish. We can take a step forward if someone accompanies us.

I want to tell you from my experience that the dementia journey can be delightful and fruitful. We, the people living with dementia, have no time to wait or to waste. Postponing support and legislation will never provide us with hope. It is a fact that anyone can get dementia. If we own this, rather than thinking of it as someone else’s problem, the world would be better place: not only for people living with dementia, but also for people living with other diseases and disabilities.

People living in harmony with each other makes life better for everyone. Having dementia does not mean the end of life. We, the people living with dementia, do have a future, although we may be “just one step ahead of others in our dementia journey.”

This article was originally published in “Living with Dementia : Voice of Asia (English)“.