Japanese Dementia Café and the Family Association culture

Japanese Dementia Café and the Family Association culture

The beginning and spread of the Japanese Dementia Cafés

It was Christmas 2011 when professor Satoko Hotta of Keio University Graduate School, who finished her research studies abroad, presented the Alzheimer’s Café in the Netherlands during the morning’s debriefing session. It attracted stakeholders from the public and private sector who gathered the concept of “people with dementia, families, local residents, and professionals sharing a place on an equal footing.” This initiative, which later was translated as “Dementia Café,” spread throughout Japan with the citizens’ volunteer spirit and the government’s support.

A big café “Tsuchihashi Café” where more than 100 people gather (Kawasaki City, Kanagawa Prefecture)

A café on the sea “Nami-nication” (Kamakura City, Kanagawa Prefecture)

The government has announced that there are 7988 dementia cafés in the country as of March 2020. However, the exact number is unknown, as it does not include small cafés that are not publicly financed, and it seems that some municipalities are over-counted.

What is certain is that Japan’s dementia café has grown into a unique activity that is unparalleled in the world in terms of size in the present time. I’m probably the only journalist in Japan who specializes in covering Dementia Cafés. As yet, there is a list of 6300 opened Dementia Cafés; I have visited 240 and included 60 in video works.

Furthermore, I wrote a book in June 2020. It is a guidebook that covers Dementia Cafés all over Japan with simple text and colorful pictures. The book lists 28 cafés based on its original classification. Among many examples of big cafés where more than 100 people gather, cafés in private houses, cafés in museums, cafés in the sea, etcetera. The first one in the publication order was the “Ishikura Café” in Utsunomiya City, Tochigi Prefecture.

”Ishikura Café” as a symbolic existence

“Ishikura Café” (Utsunomiya City, Tochigi Prefecture)

” Ishikura Café” was one of the very first dementia cafés in Japan. The reason for its creation was Mr. Yukihiro Sugimura, a member of the Alzheimer’s Association Japan(AAJ), Tochigi branch, who had young-onset dementia. In July 2012, Mr. Sugimura, who wanted to be beneficial to society even with dementia, started a café in a stone warehouse on the banks of Kinugawa River with his friends. Along with “Dementia Café” in Kunitachi City, Tokyo, which started in the same year, “D Café Lamiyo” in Meguro-Ku, Tokyo, and “Orange Café Imadegawa” in Kyoto City, “Ishikura Café” is a pioneer of dementia cafés in Japan.

Among them, Mr. Sugimura and “Ishikura Café” became iconic. The media paid attention to Mr. Sugimura. Who worked hard as the café owner when still there were few people known with dementia who were working actively. In particular, it was repeatedly taken up as the theme of the dementia awareness campaign of NHK, the largest TV broadcast in Japan. A large audience knew the existence of dementia cafés with the message that “living with dementia is not the end.”

After that, at “Ishikura Café,” not only drinks and cakes were served but also lunch, the number of cooking staff increased, and they could connect with local farmers who would donate vegetables for that purpose. The representative, Mrs. Shigeko Kanazawa, said, “There is nothing you should not do here.” Even though professional singers and volunteers who teach origami had not come to the café, people with disabilities have joined to make decorations and items for sale in the store.

Family Association Culture as a source

In my book of 2020, I categorized Japanese Dementia Cafés into “Spread Cafés” and “Specialized Cafés.” Concisely speaking, the “Spread” category incorporates those cafés that expand the range of activities. At the same time, they change, whereas the “Specialized” category alludes to those that polish their style without uncertainty. For example, the former representative, “Ishikura Café,” gave me the inspiration for this classification. A typical example of the latter is the Dutch Alzheimer’s café type initiative. They show clearly what to do and what no to reach the ideal of continuing the café without changing for 10 to 20 years.

Perhaps a functional and consistent “Specialized Café” is more compatible with the insurance system and dementia policies. On the other hand, the ad-hoc “Spread Café” may look like an amateur do-it-yourself structure. However, what separates the two is the difference in values regarding the independence of “whether the café fits the person or the person fits the café,” not the superiority or inferiority in essence.

I feel that Japan’s domestic view of interpersonal support is reflected in the characteristics of the “Spread Café” that “fits to the people” and “changes its shape with flexibility.” One of the sources of this is the Family Association activities that have listened to each and everyone’s voices like the “Ishikura Café” opened by Alzheimer’s Association Japan(AAJ), Tochigi branch.

It has been about ten years since Alzheimer’s Café was introduced to Japan. While respecting everyone who has created the culture of Dementia Cafés that is unprecedented in the world, I would like to continue to convey this unique initiative.

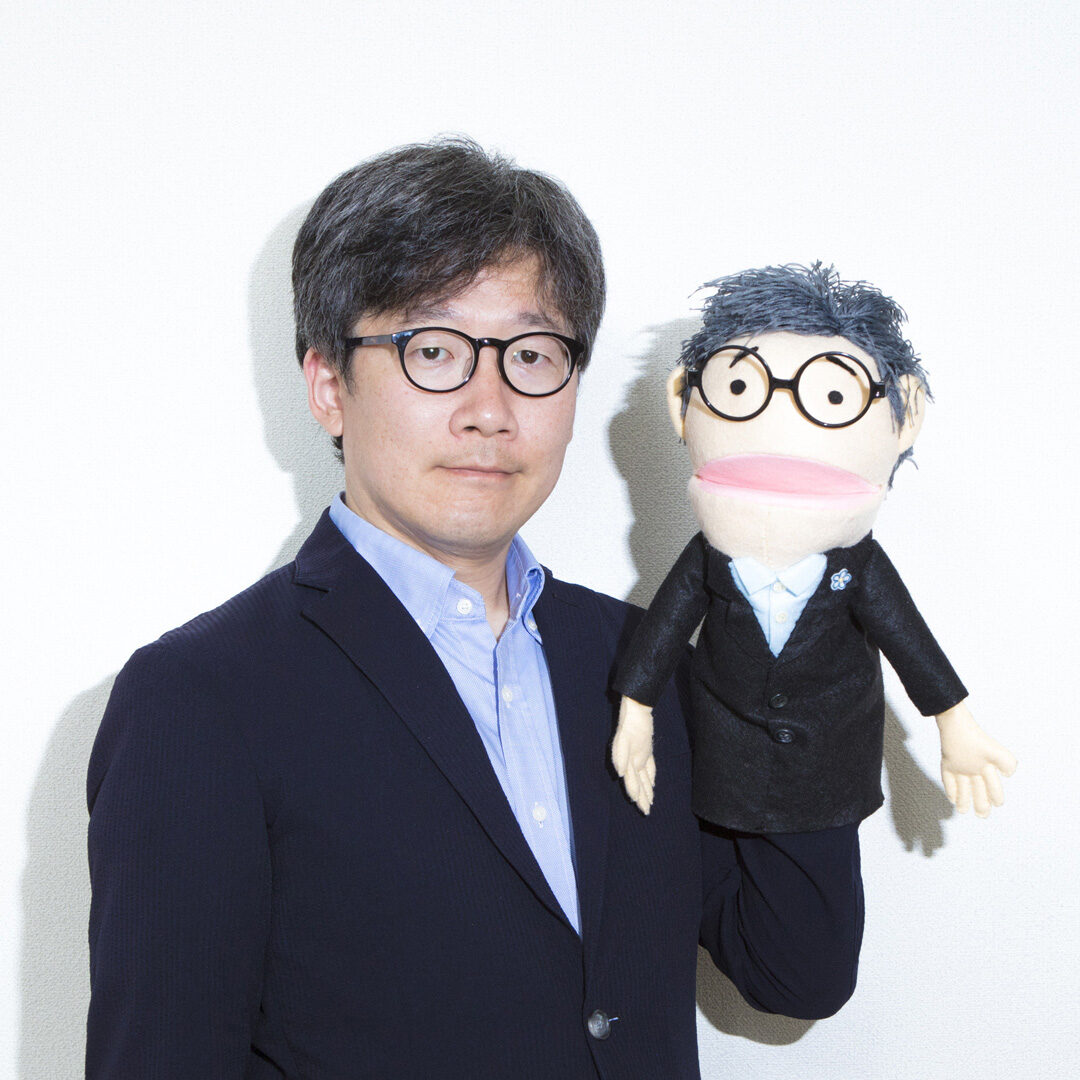

<< Author’s profile >>

Soichi Kosuga.

Photographer. Journalist. Author of “Guidebook to Ninchisho-Cafes in Japan” (Creates Kamogawa, 2020). Reporter of Nakamaru by Asahi Shimbun (https://nakamaaru.asahi.com/)

<< Contact. >>

Email address: kosuga_desuga@hotmail.com