Richness of emotion in people with dementia.

Richness of emotion in people with dementia.

By Ayako Onzo (PhD. The University of Tokyo)

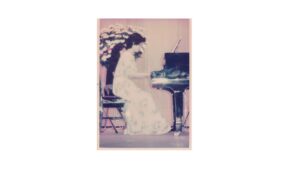

My mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2015 at the age of 65. Since then, I have lived with my mother and observed her for about eight years until she died in 2023. Many studies have suggested that with dementia, personality changes occur, and that verbal and emotional expression becomes less and less with the progression of the disease. However, even after my mother was diagnosed as ‘severe’ in 2021, she showed rich emotions in the house and tried to take care of me until the end. Through my experience with my mother, I have come to believe that dementia does not change who they are.

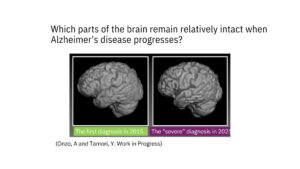

It became my aim to prove this scientifically. What can our brains tell us? In Alzheimer’s disease, typically the hippocampus is known to atrophy from the early stages, but what about the brain regions outside the hippocampus? When I looked at my mother’s brain images, indeed, the hippocampus was greatly atrophied in 2021. However, some areas appeared relatively intact.

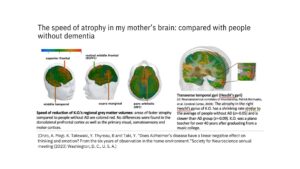

With the help of Professor Yasuyuki Taki and his colleagues at Tohoku University, we were able to compare the speed of atrophy of each cortical area in my mother’s brain with that of people without dementia. We found that the Heschel gyrus, known to be related to musicianship, was preserved in my mother’s brain. She was a piano teacher and has loved music since she was a small child. This could be evidence that even with dementia, what you have spent a lot of time on is not lost.

Another surprising finding was that some higher brain regions may also be preserved. For example, the speed of atrophy of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), a region that is highly correlated with IQ and is said to be responsible for human intelligence, was the same in my mother and in people without dementia.

So, there were brain regions that were less vulnerable to damage from dementia. In these areas, the DLPFC was included. The function of the DLPFC might be to exert a will to somehow live by mobilising the abilities of the parts of the brain that are left to you. Although this result was of N=1, limited to my mother, a variety of abilities and emotions may remain in people with dementia.

In this study, together with Dr Mikiko Oono at National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Dr Shuji Tsuda at Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Geriatrics and Gerontology, and Professor Satoko Hotta at Keio University (also the Representative of Designing for Dementia Hub), we decided to extend the research to people other than my mother and investigate the emotional richness that remains in people with dementia.

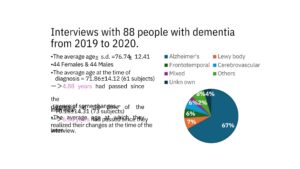

Designing for Dementia Hub has interviewed more than 100 people with dementia so far and has created a database that provides stories told by people with dementia. Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. The interviews covered everything from the difficulties people with dementia feel in their lives to their hopes for the future, which have been left in written form.This time, we analysed the emotions expressed in the transcription of 88 interviews conducted between 2019 and 2020. At the time of the interviews, these 88 people had been diagnosed for an average of 4.88 years. It is noteworthy that almost five years after diagnosis, people with dementia were still able to express a lot in words.

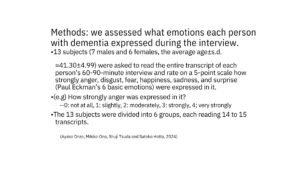

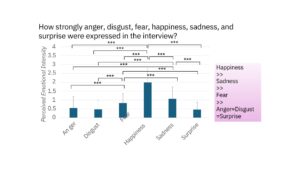

As methods, 13 subjects without dementia were asked to read the transcript of 88 interviews, and for every interview with one person, they were asked to rate how strongly emotions (anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness,and surprise – the six basic emotions defined by Paul Ekman) were expressed in the interview on a five-point scale. As a result, the emotion most strongly expressed in these interviews was happiness.

Dementia is still often associated with feelings of fear and anger. However, in contrast to these general images, what was expressed in the interviews were feelings of happiness. This is considered an important result.

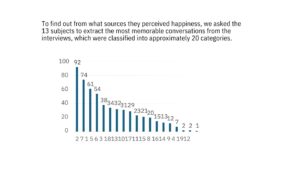

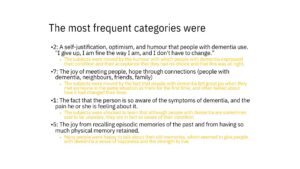

To find out from what sources they perceived happiness, we asked the 13 subjects to extract the most memorable conversations from the interviews, which were classified into approximately 20 categories. The most common category was self-justification, optimism, and humour that people with dementia used. The subjects were moved by the humour with which people with dementia expressed their conditions. The second category was the joy of meeting people. Many people with dementia mentioned that their lives had been changed by meeting for the first time someone with the same conditions as them. And another common category was the joy from recalling episodic memories of the past. Many people with dementia recalled past events with happiness, and the subjects were moved by the possibility that remembering the past could create feelings of happiness and give them the power to live.

Earlier, we said that people with dementia expressed happiness most strongly in the interviews, and it is thought that this happiness is something that they have managed to grasp by accepting their condition, making an effort to meet new people and devising their way of living.

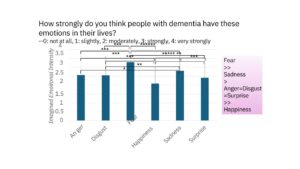

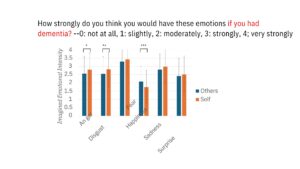

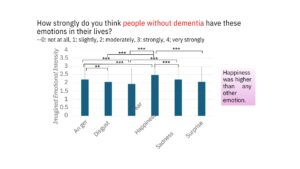

On the other hand, when the general public was surveyed on Ayako Onzo’s X (formerly Twitter) account (@ayakoonzo) and was asked what emotions they thoughtpeople with dementia would usually feel in their lives, many imagined that people with dementia would feel fear strongly and happiness most weakly. This may not be the reality of people with dementia. In contrast, when we asked the general public what emotions they thought people without dementia would usually feel in their lives, they said that happiness would be the strongest. In other words, in the public’s image, people with dementia live with fear and people without dementia live with happiness. However, in reality, at least as far as we lookedinto the interviews, people with dementia live with the strongest feelings of happiness, just as people without dementia do.

Ayako Onzo

Ayako Onzo received her Ph.D from Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2007 in the field of cognitive neuroscience. Her mother, with whom she had lived all her life, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2015, and since then she has observed her mother daily at home, both as a daughter and as a neuroscientist, and has become convinced that even after the progression of dementia, her mother’s personality remains. A documentary about her and her mother was broadcast on NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) in January 2023 and has been translated into English and is currently available worldwide under the title of “My mom has dementia: A neuroscientist’s care diary.”